Cryptographic Reality - part 2

Private vs Shared Systems of Reference

This is the second post in the series on Cryptographic Reality. The first one introduced a tension between, on one side, an external, objective reality where empirical science operates; and an internal, subjective one where formalised models are ideated. The result is an apparent paradox, or loop, in our access to reality. Is one of these reality grounding the other?

In this second post, we lean on computational theories of mind to refine the framing of this existential puzzle.

Interestingly, the original draft precedes the GPT revolution. I’ve decided to leave it as is, although much more could be said today. I believe the concepts introduced here can for instance prove useful when trying to make sense of accumulated layers of simulacra.

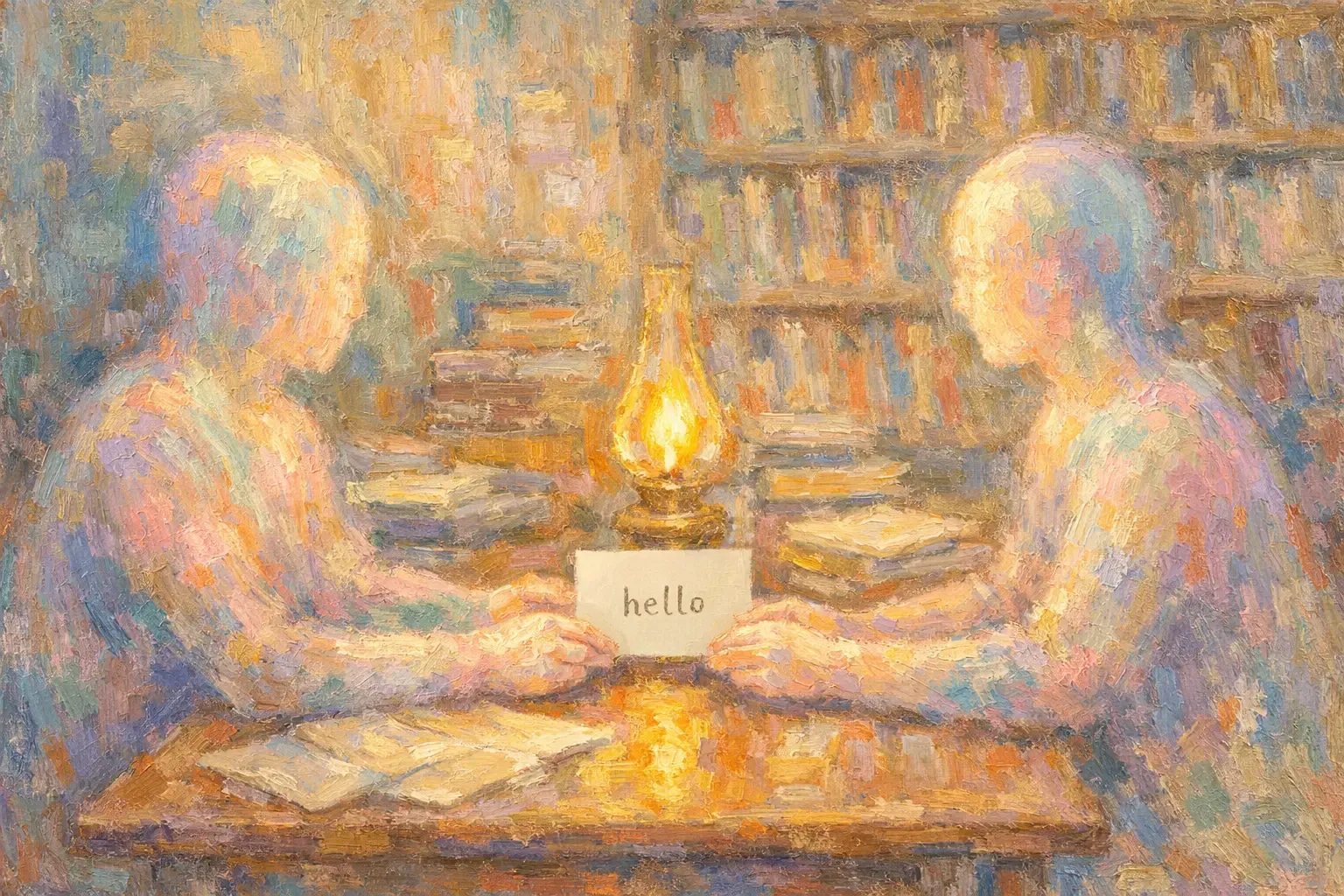

| Figure 1 Alice and Bob sharing a word

| Figure 1 Alice and Bob sharing a word

The computer revolution and the mind-body distinction

Human behaviour results from the unique combination of innate properties, “the initial state”, together with acquired ones, accumulated through life. When the behaviourist trend failed at giving a complete predictive model of human activity, linguists and cognitivists turned to computability and algorithmics to enrich our scientific understanding of intelligence (https://www.cs.princeton.edu/~rit/geo/Miller.pdf). Meanwhile, the first electronic computers also marked the birth of artificial intelligence, opening a whole new area of instrumental experimentation and mathematical formalization to further investigate the interactions between mind and matter.

At a theoretical level, the Von Neumann artefacts sparked a glaring analogy with nature’s architecture: roughly, that our senses encode external inputs while we output an external behaviour, and that our brain acts as the central processing unit running our mind, the software. Additionally, Alan Turing’s visionary model of a computing machine mechanically bridging logic to algorithmics, and its equivalent characterization in automata theory, had further widened the scope of available allegories to capture mentality.

During what is now called the “Good Old-Fashioned AI” (GOFAI) era, intelligent agents were often schematically conceptualized by state machines. Correspondingly, innate properties were tacitly captured by the initial state of the programmed agent, while any subsequent state was defined through the acquisition of inputs upon its interactions with the world. The syntactical structure, specified by the current state or configuration of the Turing machine, characterized a personal identity. Thereupon, psychological states had found an alley for their mathematical formalization. And because absolute meanings seemed plausibly describable through logic and computations, the ancient concept of a lingua mentis, a universal innate language, was revived.

Experimentally however, the first AI systems followed rudimentary specifications imposed by the limitations in computing power and memory, constraining efficient AI to operate under closed logical rules. These systems inspired several objections against the computer analogy. John Searle formulated the Chinese Room thought experiment to prove the lack of intentionality in software. According to his view, still widely held today, computers mindlessly perform syntactic manipulations of symbols and are therefore incapable of genuine understanding. The capacity to grasp intuitive meaning is a privilege reserved to natural minds. Furthermore, early computationalist theories of mind were still perplexed by the problem of reference, which depending on their implementation could lead to multiple realizability (a debate notoriously articulated by Hilary Putnam and his student Jerry Fodor in the 70s-80s).

Enthusiasm for these views faded during the winter of AI, just as technologies failed to deliver their original promises to match or surpass our natural capacities.

Contemporary computational theory of mind

Recent developments in formal models of the mind motivate a renewed understanding of the Von Neuman analogy. The underlying impulse remains unchanged. Formalization externalises subjective meaning through symbols and operations, but more importantly it aims at providing an unequivocal representation of this semantic hold. Meanwhile, empirical science assumes this world to be measurable, quantifiable – and therefore, mapping to bits of information. Consequently, progress in artificial information processing systems keep inspiring our understanding of mentality. A notable example is found in Roger Penrose’s argument (already mentioned in the post providing a short intro to phil of ai).

Contemporary AI, thanks to increased computational power and data storage capacities, uses more complex techniques than in the GOFAI era. It is no longer confined to carefully crafted sets of instructions designed to build-in a representation of the situation to the artificial agent. Instead, current models assimilate mental operations to dynamic information systems: enactive, embodied, predictive agents1. Each of the system’s state acquires or integrates information from its informational environment, constantly updating through a feedforward loop - the faculty of learning. Hence, at any given time, the current state of the system generates a representation of the world which, at least by elimination, defines itself in the world.

As was introduced in the first post, when trying to untangle subjective from objective realities, one major difficulty consists in avoiding the pitfall of circularity. To this end, we introduce a distinction between private and shared systems of reference.

Private reality: internalising external signals

Let us now update the mind-computer analogy to align with the contemporary framework.

When a new-born comes to existence, they are unable to express intelligible thoughts. But progressively, upon trial and errors, they will learn to recognize faces, shapes, and sounds, as well as how to modulate their own behaviour to act upon their environment. Their initial “blank slate” (or should we say “grey”?) continuously processes information, updating the overarching information system.

Regularities, similarities, reinforce the patterns they imprint on the mind, shaping future interpretations. Over a sufficient amount of repetition, a signal will become easier to process, so much that it might go unnoticed, requiring less efforts and attention, delegated to the subconscious. This is evident in the acquisition of sensorimotor abilities such as walking or writing. But the same reinforcement of information processing patterns also occurs at higher levels of abstraction, for instance when learning to manipulate complexifying mathematical or musical notions.

Initially, publicly available, external signals are garbled. But over time, thought after thought, each cryptographer builds their unique referential system, encoding their private access to reality, allowing smoother decoding2.

It is worth noting here that private reality is not restricted to natural minds. One could speak of the private reality of a material object, such as a rock, without endorsing panpsychism. Setting aside the debate over intentionality, free will and agency, when rain erodes the rock, or volcanic activity melts it, the system evolves – it “learns” (although such fuzzy instances are worthwhile noting, they do not match the scope and purpose explored here).

The concept of private reality, although well suited to identify phenomenal states, neither presupposes nor require their realization: it applies to any concrete information system. It is useful to delineate the subjective references of any individuated information system within an abstract specification3.

Shared reality: externalising internal processes

Complimentary to private is the concept of shared reality.

When Alice and Bob exchange the message “hello” on a piece of paper, they share more than a physical object. They also rely on culturally reinforced patterns: letters from a common alphabet, a trained ability to recognize them in the specific font which was employed to print them, the significance of a word inferred over countless of different contexts. They do not share the exact tactile experience perceived by Alice when she held the paper between her fingers, or her perhaps latent sense of self as she was reading it. They can however share an experience of holding this paper, the ability to tell if it was thin or coarse.

Shared reality involves multiple realizations, multiple perspectives, multiple sources of specification. But at the same time this overlap of distinct perspectives provides more accuracy in the capture of its absolute object. It unifies subjective distortions by triangulation across private systems of reference.

Both concepts denote relative systems of reference. A private system of reference is only defined in relation to a single interpretative origin. Whereas a shared system of reference is related to interacting systems.

Just like a rock, the piece of paper has its own private reality. The shared reality of a message being handed is not only formed by Alice and Bob’s perspectives, but of each self-encapsulated piece of information being shared by the system under scrutiny.

Shared reality lies at the intersection of interactive surfaces. It acts like an interface, connecting and translating between different information systems.

**

The concepts of private and shared reality shift the view from the traditional split between internal representations and external facts to a dynamic network of individual branches diverging from overlapping anchors.

The views raises many questions, which we will explore in a future post…

Footnotes

-

That is not to say that AI models are built on these principles, nor to say that all scientific models of mind adhere to these principles. Simply, this is our most advanced understanding of a large body of evidence and experimental work. See the thread on “the embodied mind” for more details on this. ↩

-

This notion may justifiably evoke algorithmic compression to technical readers, and will deserve its own, separate, discussion. ↩

-

We are not concerned at this stage by whether an accurate mathematical specification is achievable, or whether concrete information systems are computable, although we will consider these questions later on. ↩